|

EQUINE LAMINITIS by Robert A Eustace FRCVS Abstracted from the scrutineered veterinary journal In Practice July 1990 pp156-161 |

|

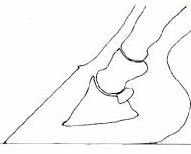

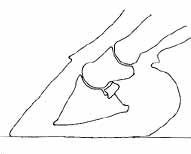

Introduction. Laminitis is one of the most common causes of lameness and disability of horses and ponies in this country. This article describes some of the gross pathological changes, recommended radiographic technique and aims to provide some practical advice on treatment. Terminology. LAMINITIS is a disease associated with ischaemia of digital dermal tissues, it is not primarily an inflammatory disease; hence lamin-itis is a misnomer. The bond between the dermal and epidermal laminae (the inter-laminar bond) is the only means of support of the distal phalanx within the hoof. If sufficient inter-laminar bonds are destroyed the animal becomes FOUNDERED ie; the pedal bone moves distally within the hoof. A SINKER is an animal whose foot has suffered complete destruction of the inter-laminar bonding and the pedal bone is totally loose within the hoof. FROG SUPPORT means providing support over the frog of the foot so that it acts as an arch support when the limb is loaded. It does not mean using such a thick frog support that the horse is forced to bear most of the weight on his frog. This will worsen the lameness in most cases. The frog should be trimmed before fitting frog supports. Causes. The cause of laminitis is unknown; the following situations are known to frequently precede an attack of laminitis. Animals in these situations can thus be regarded as at HIGH RISK from laminitis. These situations may occur singly or in combination. 1. Obesity / Overeating. The most common type seen in GB. Many animals perform no work and are used as garden ornaments by people with limited understanding of horse management. Horse owners are encouraged to overfeed their animals by feed companies, show judges and peer pressure. Native ponies require very little to eat and are unable to cope with fertilised cattle pasture. 2. Toxaemia. Any systemic disease involving a septic or toxic focus i.e., pneumonia, pleurisy, diarrhoea, colic (particularly following colic surgery), purulent metritis. Effective treatment of the initiating cause must be accomplished before improvement in the laminitis can be expected. Bacterial, viral, plant, chemical, and fungal toxins have been implicated. 3. Trauma / Mechanical. Fast or prolonged work on hard surfaces i.e., jumping ponies in summer, racehorses on firm ground, inadequately fit endurance horses are at high risk. Following overzealous foot dressing or improper shoeing causing sole pressure. Following a non-weight bearing lameness, the contralateral limb may founder. Improper foot dressing of chronic founder type 1 cases allowing either, a build up of hyperplastic laminar horn beneath the front part of the wall, or excessive heel growth leading to a broken forward phalangeal axis; both these will lead to chronic or recurrent bouts of lameness. 4. Iatrogenic. The administration of corticosteroid drugs to susceptible or stressed animals can induce laminitis. Although corticosteroids do not induce laminitis every time they are used, there is a real risk which should be made clear to the animal's owner before treatment. Corticosteroid induced laminitis usually rapidly progresses to acute founder or sinking. The administration of long acting corticosteroids, such as triamcinolone and dexamethasone, to fat ponies to treat sweet itch is particularly dangerous. Even mixtures of drugs containing corticosteroids can cause laminitis. The use of corticosteroids to treat laminitis is absolutely contraindicated. 5. Hormonal. Some laminitis cases appear to be hypothyroid although the indiscriminate use of thyroxine supplementation without testing is not recommended. Elderly animals often develop neoplasia of the pars intermedia of the pituitary gland. This manifests as a failure to shed the hair coat in the spring, the coat becomes long and fine or matted. The animals are often polydipsic and may be diabetic. Laminitis is a common sequel to such tumours. Measurement of T3, T4, insulin and cortisol following injection of thyroid releasing hormone is a useful test for both thyroid function and pituitary neoplasia. 6. Stress. Any stress such as overworking unfit horses, prolonged travelling in hot (or cold) conditions, anthelmintic treatments (particularly double doses of pyrantel) or vaccination may result in laminitis in some animals. Certain cream treatments for the treatment of sarcoids seem to be related to the onset of laminitis and founder. Some myths refuted. Drinking cold water after exercise may cause colic but not laminitis. Allergies; there is little evidence that hypersensitivities are causally related to the development of laminitis. Pregnancy; pregnant animals can develop laminitis just as easily as barren animals. Oestrus; there may be a relationship between oestrus and laminitis in some animals, however these cases are rare and changes in diet and management may prevent such cases. Heat in the feet; a very unreliable diagnostic indicator. Foot temperature normally varies throughout the day. Standing in streams or cold hosing; although the numbing effect of cold water may appear to make the animal more comfortable initially, prolonged cold will exacerbate vasoconstriction and further reduce dermal perfusion. It is doubtful whether hot or cold applications makes a significant difference to the outcome of a case. If the owner must do something, it is preferable to use warm fomentations. Hereditary predisposition to laminitis; in this country is unproven. However families of animals often have the same owner whose predisposition to recurring poor management is certainly proven. Laminitis does not just affect the front feet. Just the hind feet may be involved, or one foot or all the feet. Pathological Anatomy. The important features seen in a sagittal section of a normal digit (Figure 1a) are; 1) The top of the extensor process of the distal phalanx is slightly below the top of the dorsal hoof wall, range 0-10 mm, (Cripps and Eustace 1999). 2) The coronary groove (cg) containing the coronary corium and coronary plexus is oval in shape. 3) The dorsal cortex of the distal phalanx is parallel to the dorsal hoof wall. 4) The horn tubules (T) in the dorsal hoof wall run in straight lines down to the ground surface. 5) The solar margin of the distal phalanx is at an angle of 5-20 degrees to the ground. 6) The apex of the trimmed frog extends dorsal to the dorsal limit of the insertion of the deep digital flexor tendon. 7) The horny sole is concave. |

||

|

Initially during the prodromal phase of laminitis the laminae stretch resulting in a sagging down of the distal phalanx within the hoof. If the laminar insult is severe enough, or the animal is forced to walk, interlaminar bonds will break and cause further downward movement of the distal phalanx i.e., the animal founders. The force of this downwards movement is most dramatically seen in the coronary papillae. These will either be bent through an angle of up to 150 degrees or actually be pulled out of their sockets in the epidermis (Plates 1a & 1b). In the early stages of acute founder it can be seen that the 'rotation' of the distal phalanx is in fact a reverse rotation of the hoof in relation to the distal phalanx. Following stretching and detachment of the inter-laminar bonds fluid extravasates into the spaces created between the dermal and epidermal laminae. The parallel relationship between the dorsal cortex of the distal phalanx and the dorsal hoof wall is lost. However the alignment of the three phalanges has not changed i.e., there is no true rotation. The haemorrhage and serum accumulation below the hoof wall is under pressure and creates great pain. A dorsal wall drilling procedure will remove this fluid. In some laminitis cases the deep digital flexor muscle appears to go into spasm or actually shorten. It then becomes impossible to re-align the phalangeal column by foot dressing. Surgical division of the inferior check ligaments or deep digital flexor tendon will be necessary. A sagittal section of the digit of a foundered horse (Figure 1b) shows that the coronary corium has become squeezed between the top of the hoof wall and the front of the distal interphalangeal joint and extensor tendon (E). Unless the dorso-proximal hoof wall is thinned, or a groove drilled below the coronary groove, to relieve the compression on the coronary corium the blood supply cannot re-establish and create new wall horn. This is why untreated foundered feet have divergent growth rings with less horn formation at the toe than the heels. Many neglected animals survive an episode of acute founder to be left with the distorted feet of chronic founder. If finances preclude more effective treatments then the gait of these animals can be vastly improved by correct foot dressing and shoeing. It is important to dress the feet forward properly so as to restore the parallel relationship between the dorsal cortex of the distal phalanx and the dorsal hoof wall. This often means rasping right through the wall proper into a mass of hyperplastic laminar horn which then shows as a buff coloured crescent at the toe of the foot (Plates 2a & 2b). If having dressed the foot forward there is no wall left at the toe, leaving the animal standing on it's sole, you must fit a shoe with good cover and length with upright heels and a seated out toe. Case Assessment ; Laminitis and Acute Founder. Palpate the digital arteries for increased volume of pulsation; increase in volume indicates either an inflammatory condition within the foot or laminitis. Palpate the coronary bands for the presence of depressions; an abnormal depression indicates that the bone has moved due to weakening or loss of inter-laminar bonding. If a depression extends to the toe-quarters, the animal has started to founder. The farther back the depression can be felt towards the quarters and heels the worse the degree of founder. If the depression exists all the way back to the heels the animal is a sinker and requires immediate specialist shoeing and possibly surgical treatment within 72 hours if the animal is to have any chance of resuming an athletic career. Sinkers do not adopt the classical laminitis stance and are often misdiagnosed as azoturia. Most laminitis cases will respond to treatment with frog support, NSAID, Phenoxybenzamine (or acepromazine as second best) and confinement in a well bedded stable. Concurrent advice on feeding and management are usually necessary. Most acute founder cases will be helped by the above treatment but will require more energetic treatment (including surgical) if the feet are to be restored to functional organs. All sinkers require quick and thorough treatment if they are to stand a chance of surviving. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Figures

1a & 1b. P1; Proximal phalanx. P2; Middle phalanx. P3; Distal phalanx. Solid

arrow = palpable depression just above the coronary band. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Plates

1a & 1b. 1b; Same region as in 1a of a foundered pony. The coronary groove has become less curved, the juvenile horn tubules have been bent and are pointing skywards. In this case the coronary papillae have been pulled out of their sockets in the coronary groove and have re-aligned along the line of the dorsal cortex of the distal phalanx (arrows). |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||

|

Figures 2a & 2b. Schematic representation of sagittal sections of two digits. 2a shows reverse rotation of the hoof whereas 2b shows true rotation of the distal phalanx relative to the proximal phalanges. The degree of rotation as described by Stick et al (1982) is the same in both Figures. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Plate

2a. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Plate

2b. |

||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Plate 3a & 3b. Latero-medial radiographs of two feet. 3a is normal, compare with Figure 1a.

3b is a 'sinker'. Note the increased vertical distance between the top of the dorsal wall marker and the top of the extensor process of the distal phalanx. There is little true 'rotation' of the distal phalanx. It is common to see a linear radiolucency along the contour of the coronary band in these cases. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

|

Medical treatment. If the animal is sick treat the cause. Fluids, electrolytes and possibly antibiotic therapy are indicated in cases of diarrhoea. Endometritis cases may require manual removal of retained foetal membranes followed by repeated flushing and syphoning the uterus with warm water by means of a stomach pump and stomach tube until the effluent is clear. Generally the sicker the animal the more likely it is to founder. Phenoxybenzamine (an alpha adrenergic blocker: unlicensed for use in equines) and heparin may be used if the animal is hospitalised and blood pressure monitoring and laboratory facilities are available. These drugs are often useful to improve digital perfusion and prevent thrombosis in the acute case (Hood 1984). In the field, acepromazine (0.05-0.1 mg/kg) is a safer alpha adrenergic blocker, it helps reduce hypertension and anxiety. Dosage varies with the individual, many cases will become alternately more sensitive and resistant to the drug. A state of moderate tranquillisation is required. Of the NSAID's flunixin has some analgesic and anti-endotoxic activity and may be chosen for use in sick animals. In my experience it has less analgesic effect for laminitis than phenylbutazone (4mg/kg sid or bid for 1 day reducing to 2 mg/kg bid) or meclofenamate (2-3 mg/kg sid). Aspirin can be used singly or in combination with the other NSAID's at a dose of (2-3 mg/kg sid), it also has some anti-platelet aggregation and analgesic effects. Blood and urine samples may be taken for full haematology, biochemistry and electrolyte examinations. Electrolyte supplementation according to laboratory results seems sensible although in practice supplementation with chemical supplements has been unrewarding in my experience. A diet of alfalfa chop, straw chop, soaked unmollased sugar beet pulp and hay is recommended (Eustace 1992) to supply macronutrients. The use of a specific hoof and laminitis supplement with proven results is also recommended. General nursing care of very sick or lame individuals is mandatory if they are to retain the will to live. Radiographic technique. Latero-medial projections are the most useful. The frog of the unshod foot is trimmed to reveal the collateral frog sulci to their depths on both sides and around the tip of the frog. A drawing pin with a shortened point is placed in the frog approximately 1 cm posterior to the point of frog and its position marked with an indelible pen or scratch line across the sole and frog. (It does not matter exactly where on the frog you place the pin as long as you mark its position). The perioplic and proximo-dorsal wall horn is gently rasped to remove loose horn and create a flat dorsal surface. A straight stiff wire marker of known length is taped to the dorsal hoof wall. It is important to place the proximal end of this wire where the wall horn merges with perioplic horn, i.e., gently push the horn and place the top of the wire where the horn starts to yield. The animal is radiographed standing squarely on a flat wooden block incorporating a wire marker as a ground line. The centre of the radiographic beam should be parallel to the long axis of the navicular bone and the top of the wooden block. The height of the beam should be such as to show the ground line and the whole of the middle phalanx on the developed film (Plates 3a & 3b). Interpretation. Accumulations of fluid cannot be visualised on foot X rays. Sub-mural radiolucencies indicate the presence of gas. The most useful prognostic criterion is the measurement of the vertical distal displacement of the distal phalanx (founder distance; Eustace and Cripps 1999). This is measured by drawing two lines on the radiograph, both parallel to the ground line, one through the top of the extensor process and one through the top of the dorsal wall wire. Rotation of the distal phalanx in relation to the hoof capsule is a relatively poor prognostic indicator (Eustace and Cripps 1999). True rotation of the distal phalanx in relation to the proximal phalanges can be of prognostic significance. Figures 2a & 2b show two feet in which the angle of rotation as described by Stick, Jann, Scott and Robinson (1982) is the same; i.e. the difference in the angles between the dorsal hoof wall and the dorsal surface of the pedal bone. Figure 2a shows reverse rotation of the hoof whereas Figure 2b shows true rotation of the distal phalanx. The foot in Figure 2a requires either foot dressing or a dorsal wall resection. The foot in Figure 2b requires division of the deep digital flexor tendon to effect a cure. If done before the distal phalanx becomes osteopaenic these animals often return to soundness, even if the deep digital flexor tendons in all the legs have to be divided. These figures illustrate how meaningless it is to consider only one angle of 'rotation'. The importance of recognising and differentiating between cases of laminitis, acute founder, sinker syndrome, chronic founders type 1 and 2 cannot be over-emphasised as each carries a very different prognosis (Eustace 1992; Eustace and Cripps 1999). |

|

Do's & Don'ts Do's Do treat laminitis with the same urgency as colic. Do remove or treat the cause. Laminitis requires medical, shoeing and sometimes surgical treatments in combination. Do palpate the coronary bands and provide frog support on your first visit. Do provide the animal with a deep bed and let it lie down if it wants to. Do provide frog support with either a roll of bandage, Lily pad, heart bar shoe or plastic heart bar shoe. Do use ACP in combination with frog support. This will allow you to prescribe a lower dosage of NSAID. The toxic side effects of NSAID's are important particularly in ponies and sick or elderly horses. Do provide frog support to high risk horses. Fracture or severe sepsis cases causing non-weight bearing lameness require support on the contra-lateral limb. It is tedious to say the least to spend hours in theatre on fracture or colic cases to have them founder 10 days later! Do radiograph the feet with markers if the animal shows the same or an increased level of pain 3 days after the onset of laminitis. Do consider the relative heights of the coronary band and extensor process on radiographs. This has more prognostic relevance than 'rotation' of the distal phalanx. Do attend with the farrier if a dorsal wall resection is necessary. Although this should be a painless and bloodless procedure not requiring anaesthetic it does require veterinary supervision. Only a veterinary surgeon may perform surgery on horses. Do consider the use of a securely fitted muzzle as a management aid in dieting ponies which can then be allowed exercise without the risk of overeating. Do be wary of fitting heart bar shoes to animals receiving analgesic drugs, less sensitive feet cannot respond to excessive shoe pressure. Do encourage clients to insure their horses with a reputable company against veterinary fees as hospitalisation of severe cases can be expensive. Do consider early referral of unresponsive cases. Don't's. Don't use corticosteroids. Don't force exercise the animal. Exercise was thought to be beneficial by increasing the blood flow to the foot. There is already a tremendous increase in the blood flow to the foot but there is little or no perfusion of the dermal laminae. No amount of exercise will improve this situation and may well mechanically tear the remaining laminae thereby worsening the founder. Don't remove large amounts of heel from acute founder cases, (including chronic founder type 1 cases suffering a secondary acute founder attack). this increases the tension in the deep digital flexor tendon and may result in more 'rotation'. First test by placing a wedge (equivalent in height to the amount of heel to be removed) beneath the toe of the foot and raise the contra-lateral limb. If the animal is more uncomfortable of if a depression appears at the dorsal coronary band, leave the heel alone. Don't remove the shoes (other than to fit heart bar shoes) if the animal has a flat or convex sole. It will be more uncomfortable having to stand on it's sole. Don't fit any shoe other than a correctly fitted heart bar shoe to foundered horses. If the animal has foundered, the bone is loose within the hoof. The higher you raise it from the ground by means of non-support shoes, the farther the bone has to move downwards. Don't fit any device that applies pressure to the sole of the foot, it is not designed as a weight bearing structure and will easily bruise and abscess. Don't take non-weight bearing radiographs, they are of little diagnostic value. Don't ask farriers to fit heart bar shoes without you having taken radiographs using markers. Good farriers will legitimately refuse to do so. Don't forget to mark on the frog where you placed the drawing pin. If the farrier cannot appreciate where the pin was placed he is unable to fit the shoe. Don't cut holes in the soles of laminitis or acute founder cases. This will result in granulating solar corium protruding through the hole which will be difficult to control. If there is sub-solar fluid present effect drainage by entering the foot through the dorsal wall at the level of the wall-sole junction. The horny sole is your biggest ally in treating laminitis and acute founder. Don't ask the farrier to fit pads. You cannot evaluate the sole, the soles become wet due to trapped solar evaporation. Any solar pressure will further compromise the blood flow within the foot and cause pain. Don't fight to fit shoes to horses in severe pain. There are effective glue-on alternatives available. Don't provide repeat prescriptions of NSAID without re-visiting. An acute laminitis case that is in significant pain after 10 days probably requires a change in treatment or management. Don't use nerve blocks to reduce the animal's pain. The animal will further mechanically damage compromised laminae by walking on painless feet. Nerve blocks may affect the neuronal control of digital arteriovenous anastomoses and potentiate digital ischaemia. Don't hope that antibiotics will help either 'gravel' or post-founder abscesses. They won't. Only when drainage has been provided will the lameness improve. Don't tell the owner to starve the animal, some people take you literally. Feed according to the animals bodily condition. Hay and bran is a poor diet for horses and ponies. If the animal needs to be dieted do so gradually using a combination of alfalfa chop, straw chop, soaked sugar beet and hay. Beware of rapidly dieting very fat or pregnant ponies, they may develop hyperlipaemia which is often more serious than the original laminitis. Don't think that because the movement of the distal phalanx has resulted in solar prolapse that is the end of the horse's working life. It is the means by which prolapse has occurred i.e., the amount of distal displacement which is important. References.

|

||